Last week, I met with a few friends for an evening of 80s retro computing – or retro gaming to be specific. We set up an Amiga 500 and a C64 and played classic games like Lotus Esprit Turbo Challenge, Dynablaster, Sensible Soccer, California Games and International Karate.

Dynablaster

It was great fun. Retro gaming of course is a lot about nostalgia but there’s also something about many of these games that hasn’t been achieved in many modern video games anymore: Instead of stunningly realistic visuals – which of course weren’t possible at the time – those classic games rather hinge on the actual gameplay and focus on getting the most out of the respective platform and its constraints. Game and demo programmers got the most out of the limited memory resources available on that machines and by drawing upon the specific capabilities of system architectures like the Amiga’s custom chips sometimes achieved considerable feats no one would have thought possible on a machine with 64 KB of RAM (or 512 KB for that matter), one early notable example for the Amiga being Defender of the Crown, a game that showed what was possible with the Amiga back in the day.

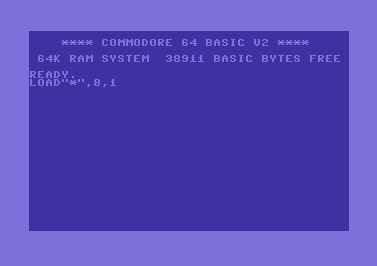

Seeing the C64’s “READY” message and the blinking cursor ▊ prompt again I realized something else though that I never fully realized or appreciated (mainly since of course I didn’t know anything about operating systems at that age and besides hadn’t anything else to compare to) when I first used a C64 in the 80s:

Because the C64 boots directly into BASIC the main user interface of the machine is an easily accessible programming environment.

Sure, this environment can be used for basic file system operations such as listing directory contents, loading files or running programs and in most cases this would have been the most common actions. However, you could instantly write, directly manipulate and run your own custom programs just as well.

Amiga OS already departed from this approach to a certain extent: The Kickstart boot loader didn’t allow you to directly manipulate instructions in the machine’s RAM. In order to program the Amiga you first had to load the Workbench, the Amiga’s main OS, which included an always-on Amiga BASIC prompt though, that could be used in pretty much the same way as the C64 BASIC prompt.

This in my opinion is a powerful notion: The computer presenting you with a blank slate, or an empty canvas if you will, to immediately fill with your own ideas and creations. Better still, the BASIC user interface is reactive and will provide you with instant feedback about your program results or errors. What you code is what you see!

This idea of programming as a user interface encourages production and creation instead of consumption, which seems to have become the most widespread use of computers – particularly of the smartphone and tablet variety – today.

This is what Steve Jobs’ now famous “Computers are like a bicycle for our minds” metaphor is about: Computers are powerful tools for realizing ideas and creating awesome products, tools, games and art.

This notion however got lost or for most users at least is buried under user interface layers. Apart from limited environments such as smartphones and tablets, you can most certainly still use commonly available computers for programming and creating stuff in general, with the programming environments and creative tools being much more powerful and sophisticated than those available 30 years ago. However, the means of creating stuff are less accessible to the average user: For writing software you have to install an IDE, set up a development environment, tooling and build system – an often cumbersome process that’s been particularly plaguing JavaScript and web development in recent years.

Interestingly, a considerable part of the allure of the web stems from the fact that right from its beginning to this day you could and for the most part still can (with some sort of a caveat applying to artefacts like minified code) simply right-click on “view source” in your browser in order to explore how a particular feature has been implemented. In that sense the web is a continuation of the idea of computing as a participatory environment that fosters creation.

Another environment that in that respect is similar to C64 BASIC is the UNIX command line: UNIX shells are Turing-complete environments that allow you to create complex software right after booting your computer and being greeted the command line prompt.

Now, this post isn’t supposed to be a curmudgeonly rant about how things were better in the past and how the computer industry lost its way when opting for graphical – and by extension multitouch – user interfaces. Quite to the contrary. Those developments and tremendous UX improvements were necessary in order to make computers accessible to a larger audience and they were pivotal in making way for computers as everyday tools.

However, computing and how we use computers mustn’t stop here. In order to truly leverage the potential of computers, user interfaces need to more readily accommodate creative endeavours and provide accessible, reactive programming tools that allow for easier, more natural creation and manipulation of content and data. This is why I’m a huge fan of Bret Victor’s work and the idea that programming tools should provide immediate, responsive feedback to your coding.

I think this is the way to go forward in computing technology and UI / UX in particular. The time for platforms like the C64 or the Amiga has certainly long since passed and UI design has made huge progress since their respective heydays but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t learn from approaches that made sense back then and still do today, perhaps even all the more so.

Deutsch

Deutsch